Weekly #22: Stop Believing the Stories You're Told—Including This One

How Great Narratives Can Make or Break Your Investment Portfolio

Happy Sunday, my fellow Sharks!

Today, we'll explore how narratives shape our perceptions—and why understanding the stories we tell ourselves is crucial to better investing.

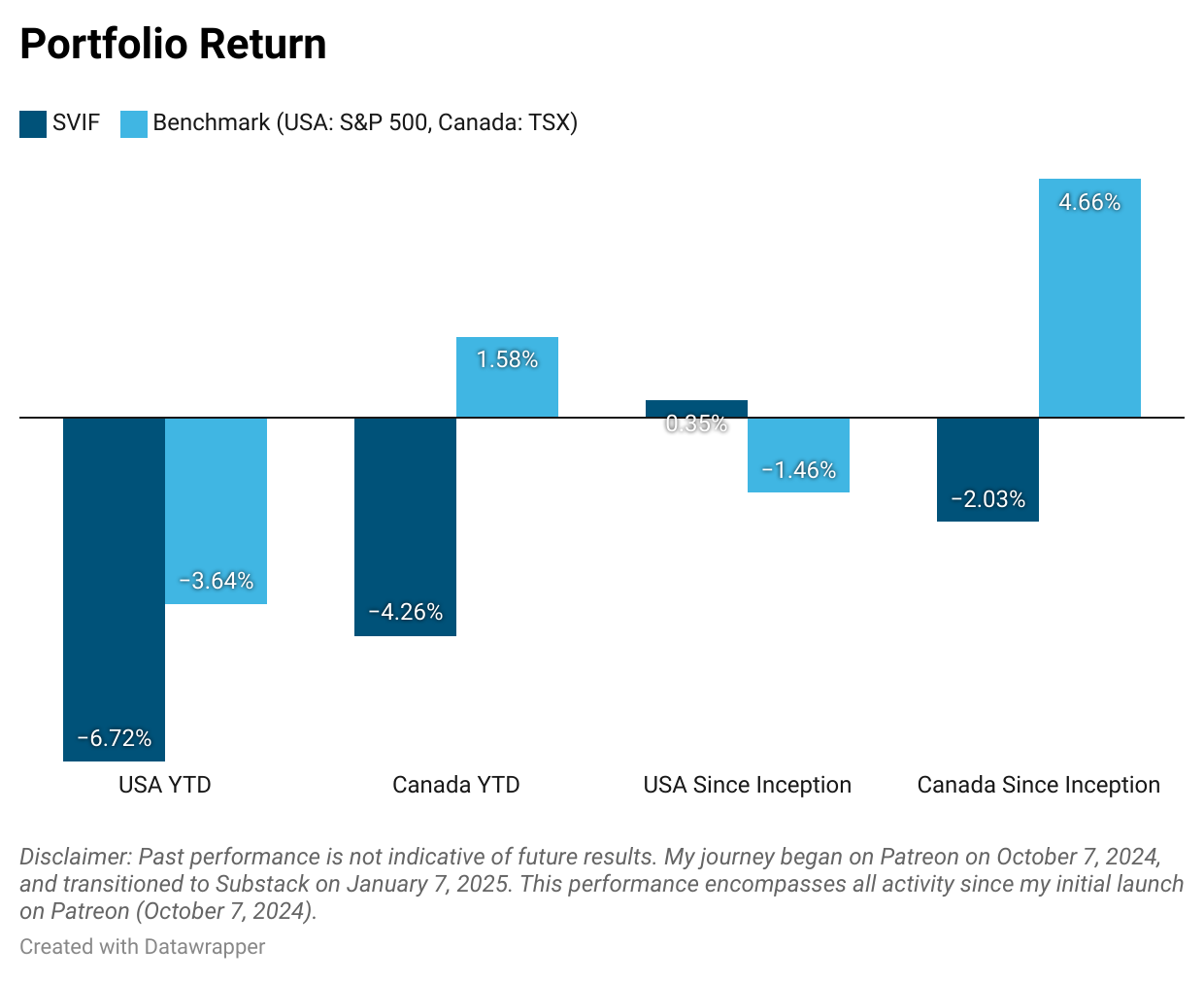

But first, let’s talk about portfolio performance. This week, our portfolios continued the recovery path. Portfolio USA improved more than the S&P 500, narrowing the gap from -373 bps to -308 bps YTD. While Portfolio Canada also recovered, its improvement was slower than the TSX, widening the gap from -555 bps to -584 bps YTD.

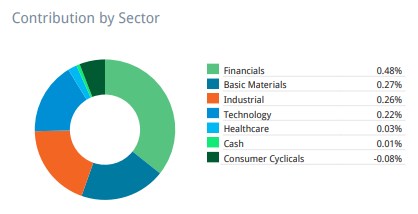

Most sectors were flattish, but Industrials, Consumer Cyclicals, and Technology led the recovery in 🇺🇸, while Financials, Gold, and Industrials led in 🇨🇦.

Portfolio USA

Portfolio Canada

Here is the weekly performance of each stock in our portfolios: Weekly Stock Performance Tracker

The Fear & Greed Index increased from 21 to 23 last week, remaining in extreme fear territory, so we should continue the strategy mentioned in Weekly #21.

Thought of the Week: Storytelling is a double-edged sword, so be careful.

Many people claim that storytelling is the main reason that humans have become the dominant species on the face of the earth. As Yuval explains in Nexus (I strongly recommend the book), there are three types of truths:

Objective truth: These truths are empirical and can be tested or observed such as “the sky is blue”.

Subjective truth: These are personal and can vary from one person to another such as “I am hungry”.

Inter-subjective truth: These are social constructs—they’re powerful not because they’re physically real, but because we agree to treat them as real such as “Money has value”. A $100 bill is just paper, but we all agree it represents value.

The most interesting type of truth is the third one. It isn’t based on empirical evidence or personal feelings—it's simply an agreement.

So, why did we collectively agree that you can exchange a $20 bill for 87 eggs in Toronto but only 26 eggs in New York?

On the surface, this seems like a question about economics, inflation, or cost of living — but at a deeper level, it’s really about belief. Why does a piece of paper with "$20" on it have the power to command food, shelter, and labour?

The answer? Stories.

The reason you can trade a $20 bill for 87 eggs in Toronto but only 26 in New York isn’t because of some natural law. It’s because, as humans, we’ve built societies around shared beliefs. We agree — collectively — that this piece of paper represents a certain amount of value. And the amount it represents depends on the local narrative: inflation, labour, supply chains, and what the community is willing to accept.

You may say “George! you are wrong! Eggs in NY are so expensive because of a severe outbreak of avian flu that began in 2022, leading to the loss of millions of egg-laying hens. This has caused a significant supply shortage while demand remains steady. Additionally, transportation costs and local market conditions have contributed to regional price differences.”

Or you might blame the high price of eggs on Biden—like some talking heads on TV do…

That's a nice explanation, but it raises the question—why is there a shortage in the US and not in Canada? You can’t sell your Canadian eggs in the US — not because they’re bad, but because we’ve agreed on a story that says only certain eggs are allowed. In the US, as per USDA standards, eggs are washed and then refrigerated immediately. In Canada, eggs are often not washed the same way and can be stored at room temperature. So even if Canadian eggs are safe, they may not meet USDA standards, so they’re not allowed across the border. It’s not physics. It’s politics, regulation, economics, and national identity — all wrapped into shared beliefs. And don’t get me started on tariffs…

Here's another story: I was born in one of the most contested regions on Earth. The region has been in a state of conflict for over 2,000 years, so living there is far from easy. Getting a good education is a challenge, and security is virtually nonexistent.

But my daughter, who was born in one of the most stable, developed countries, will enjoy a life of security, a good education and a fair chance to achieve whatever she wants to.

The objective truth is that both my daughter and I are homo sapiens, we both have one head and four limbs and we both breathe air. The subjective truth (which feels objective to me) is that my daughter has the prettiest smile in the world. But the inter-subjective truth is that she was born Canadian and I was born on non-Canadian land. This inter-subjective truth causes a drastic difference between my life circumstances and my daughter's—all because she was born in a different GPS location than I was.

Stories develop in four stages:

We invent a narrative (e.g., money = value).

We teach it to others (schools, media, government).

We act as if it’s true (using money, obeying laws, honouring contracts).

The belief becomes reality — not physically, but socially.

While this introduction might sound like I'm against stories, it’s quite the opposite—I’m a believer in stories. Without them, we'd go nowhere. Especially in investing, stories are critical. But to appreciate the good, you have to understand the bad.

Be aware of stories and don’t just naively take them in

Stories have built empires and religions. The Bible is humanity’s bestseller story that has endured the test of time. The real value of the Bible doesn't hinge on whether Jesus walked on water, but rather on how it provided humanity with a framework of values that enabled coexistence in ever-growing cities. On the dark side, that story has caused countless wars and suffering even in today’s age.

In investing, stories play a critical role and it sunk in around 2017. That is when I read Narrative and Numbers: The Value of Stories in Business by Damodaran. The book emphasizes that stories add meaning to numbers, and numbers add credibility to stories. Combining them leads to better decision-making and understanding of business.

It was a game-changer for me. I always knew stories in investing were important, but I never realized just how critical they were. Also, it allowed me to become more critical of what company management and analysts were saying.

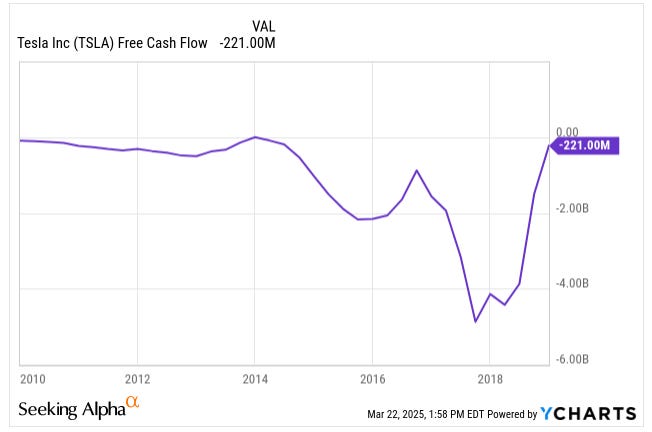

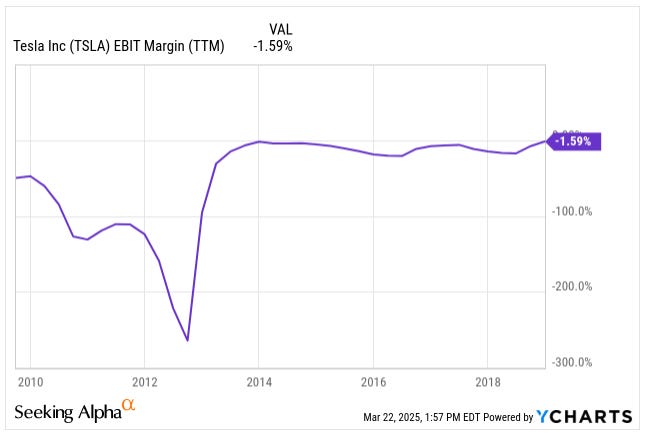

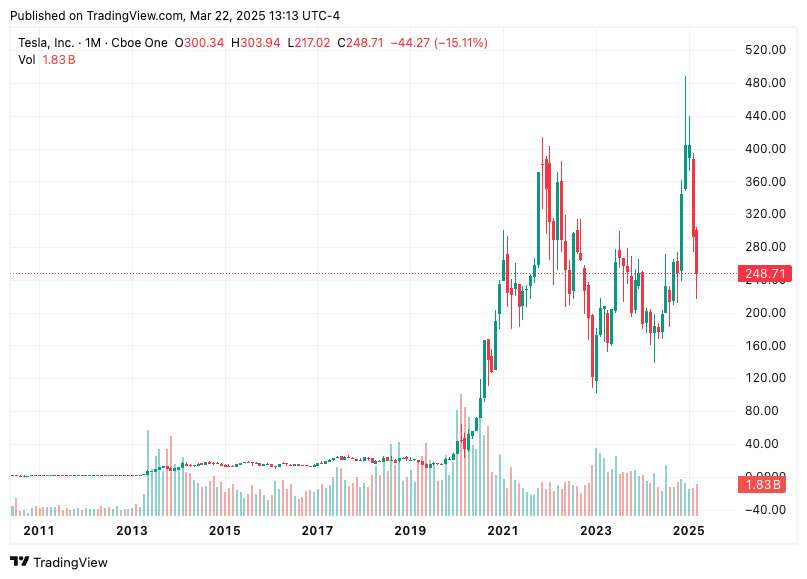

CEOs are storytellers—and sometimes, the story gets ahead of the numbers. Consider Musk. Musk created a shared belief that sustained Tesla until the numbers finally caught up.

Elon’s story inspired belief, kept employees and customers motivated, helped Tesla raise more capital when it needed it most and drove the stock price up.

But the reality was far riskier and shakier than the story suggested. Tesla could have easily collapsed had the belief from markets and investors not persisted.

In 2018, Tesla was:

Burning over $1 billion in cash per quarter.

Operating margins were negative.

There were frequent Model 3 production delays (the infamous "production hell").

Suppliers were reportedly being asked to refund payments to help Tesla stay afloat.

Tesla's own filings included "going concern" warnings — language used when a company may not be able to continue operating. Just read the Risk section in the 2017 10K filing.

Also, the 2025 sell-off of Tesla stock is driven by stories, be it related to the discontent with Elon and Dodge or BYD’s emergence in EV and taking Tesla’s share in China.

While Elon Musk’s storytelling fueled Tesla’s growth, history is filled with cautionary tales too. Take Theranos, whose visionary story attracted billions but eventually collapsed under the weight of reality. Or consider WeWork, whose growth narrative was compelling until it wasn't. These examples remind us that compelling stories alone aren’t enough—they must match the fundamentals.

And as investors, we need to remember that storytelling can set psychological traps, be it confirmation, recency or narrative bias. Being mindful of these biases can help us remain objective and balanced.

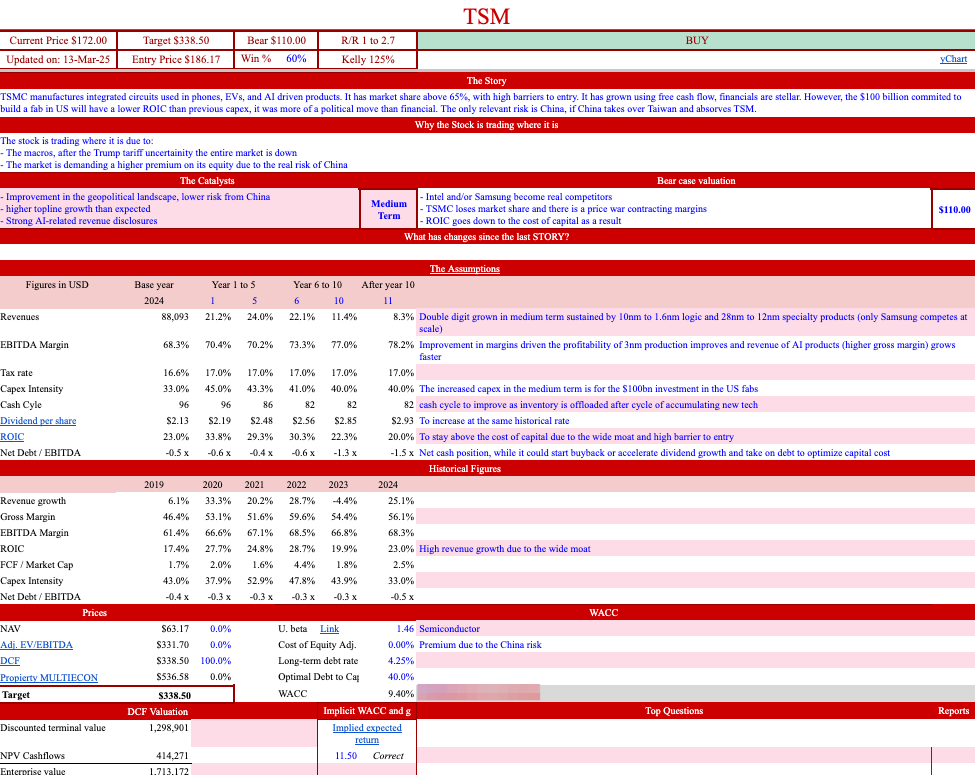

Confirmation bias makes us favour stories that align with our existing beliefs. I always question the story and put on my devil’s advocate hat. When I finish, I test it by sharing it with someone I know who has the opposite view. For example, for my TSMC deep dive, I asked my friend MJ to test my China assumptions, and he did a great job at countering all my assumptions. The result was a more balanced view and an understanding of where the story could break. If you don’t have access to such a devil’s advocate, you can feed your story to ChatGPT and ask it to do the job for you.

Recency bias makes recent, vivid stories feel more truthful than they might be. Over my investing journey, one thing I learned was that the market has a very short memory. After the dot-com bust in 2000 came the 2007 housing bubble. Investors piled into real estate and leveraged products just a few years after watching tech stocks implode. Lesson learned? Not quite.

The narrative fallacy pushes us to simplify messy, complex realities into clean, believable stories. Take job interviews, for example. When they ask, “Tell me about yourself,” you don’t say, “Well, I took the first internship I was offered, switched industries because they paid more, and then got laid off.” Instead, you craft a story—how you intentionally pursued that internship to build a skill set aligned with your long-term goals, then transitioned to a new role to keep growing, and how, in mutual agreement with your manager, you moved on to explore bigger opportunities. That is a story.

So while listening to stories, you have to question the story and the assumptions behind it. For example, I told the story of Taiwan Semiconductor (NYSE: TSM) earlier this week. It was my 7,400-word deep dive into the company. While the story may sound convincing, you have to remember it is my story of TSMC and you have to bring your judgements to my story. For example, in the story, I was convinced (I still am) that the US would win against China if they went to war over Taiwan. However, you have to question that assumption and make your own call.

Use stories to improve your investment process

After reading Narrative and Numbers, I started keeping a journal of why I am investing in certain stocks, which would ensure the numbers and story align and I would review my stories post-mortem to understand how my story compared to reality. I think this habit improved my process dramatically.

To practically apply Damodaran’s lesson, I began to use a checklist whenever assessing investment stories:

What critical assumptions must hold true for this story to be correct?

Which metrics can validate these assumptions over time?

How might competition, regulation, or consumer preferences disrupt the narrative?

Those are just three items on my checklist, you can find a more comprehensive checklist in my book.

But the stories were not just for when I started a position, but also when I closed them. In the past, whenever I closed a position, I would just move on, not questioning what went wrong or right. That was such a waste of great learning opportunities. For example, in Weekly #20, I shared a post-mortem analysis on AMPH, which reminded me to thoroughly assess competitive advantages, deeply scrutinize acquisitions, and carefully monitor patent expirations.

When monitoring your story’s assumptions, watch closely for red flags signalling trouble—such as key executives suddenly leaving, unexpected accounting policy shifts, or mounting complaints from suppliers and customers. For instance, Tesla’s 'production hell' period was marked by intense media skepticism, supplier frustrations, and executive turnover—clear indicators the reality was testing Elon’s narrative.

Investing stories should be in sync with the numbers. I keep the story in the same Google Sheet file as my valuation model, so the story and the numbers are in sync. Below is a screenshot of my TSM story, after any changes in the story or the numbers, I update the file and keep historical versions, so I can always go back and revisit the story behind why I bought the stock.

One simple improvement to your investment process is keeping a journal about why you bought or sold each stock. I guarantee that this simple habit will improve your portfolio return.

So always question the stories people tell you—even the one I'm telling you right now. And keep a journal for your investment stories.

That is it fellow Sharks!